The transaction layer of CockroachDB's architecture implements support for ACID transactions by coordinating concurrent operations.

If you haven't already, we recommend reading the Architecture Overview.

Overview

Above all else, CockroachDB believes consistency is the most important feature of a database––without it, developers cannot build reliable tools, and businesses suffer from potentially subtle and hard to detect anomalies.

To provide consistency, CockroachDB implements full support for ACID transaction semantics in the transaction layer. However, it's important to realize that all statements are handled as transactions, including single statements––this is sometimes referred to as "autocommit mode" because it behaves as if every statement is followed by a COMMIT.

For code samples of using transactions in CockroachDB, see our documentation on transactions.

Because CockroachDB enables transactions that can span your entire cluster (including cross-range and cross-table transactions), it achieves correctness using a distributed, atomic commit protocol called Parallel Commits.

Writes and reads (phase 1)

Writing

When the transaction layer executes write operations, it doesn't directly write values to disk. Instead, it creates several things that help it mediate a distributed transaction:

Locks for all of a transaction’s writes, which represent a provisional, uncommitted state. CockroachDB has several different types of locking:

- Unreplicated Locks are stored in an in-memory, per-node lock table by the concurrency control machinery. These locks are not replicated via Raft.

- Replicated Locks (also known as write intents) are replicated via Raft, and act as a combination of a provisional value and an exclusive lock. They are essentially the same as standard multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) values but also contain a pointer to the transaction record stored on the cluster.

A transaction record stored in the range where the first write occurs, which includes the transaction's current state (which is either

PENDING,STAGING,COMMITTED, orABORTED).

As write intents are created, CockroachDB checks for newer committed values. If newer committed values exist, the transaction may be restarted. If existing write intents for the same keys exist, it is resolved as a transaction conflict.

If transactions fail for other reasons, such as failing to pass a SQL constraint, the transaction is aborted.

Reading

If the transaction has not been aborted, the transaction layer begins executing read operations. If a read only encounters standard MVCC values, everything is fine. However, if it encounters any write intents, the operation must be resolved as a transaction conflict.

CockroachDB provides the following types of reads:

- Strongly-consistent (aka "non-stale") reads: These are the default and most common type of read. These reads go through the leaseholder and see all writes performed by writers that committed before the reading transaction started. They always return data that is correct and up-to-date.

- Stale reads: These are useful in situations where you can afford to read data that is slightly stale in exchange for faster reads. They can only be used in read-only transactions that use the

AS OF SYSTEM TIMEclause. They do not need to go through the leaseholder, since they ensure consistency by reading from a local replica at a timestamp that is never higher than the closed timestamp. For more information about how to use stale reads from SQL, see Follower Reads.

Commits (phase 2)

CockroachDB checks the running transaction's record to see if it's been ABORTED; if it has, it throws a retryable error to the client.

Otherwise, CockroachDB sets the transaction record's state to STAGING and checks the transaction's pending write intents to see if they have been successfully replicated across the cluster.

When the transaction passes these checks, CockroachDB responds with the transaction's success to the client, and moves on to the cleanup phase. At this point, the transaction is committed, and the client is free to begin sending more SQL statements to the cluster.

For a more detailed tutorial of the commit protocol, see Parallel Commits.

Cleanup (asynchronous phase 3)

After the transaction has been committed, it should be marked as such, and all of the write intents should be resolved. To do this, the coordinating node––which kept a track of all of the keys it wrote––reaches out and:

- Moves the state of the transaction record from

STAGINGtoCOMMITTED. - Resolves the transaction's write intents to MVCC values by removing the element that points it to the transaction record.

- Deletes the write intents.

This is simply an optimization, though. If operations in the future encounter write intents, they always check their transaction records––any operation can resolve or remove write intents by checking the transaction record's status.

Interactions with other layers

In relationship to other layers in CockroachDB, the transaction layer:

- Receives KV operations from the SQL layer.

- Controls the flow of KV operations sent to the distribution layer.

Technical details and components

Time and hybrid logical clocks

In distributed systems, ordering and causality are difficult problems to solve. While it's possible to rely entirely on Raft consensus to maintain serializability, it would be inefficient for reading data. To optimize performance of reads, CockroachDB implements hybrid-logical clocks (HLC) which are composed of a physical component (always close to local wall time) and a logical component (used to distinguish between events with the same physical component). This means that HLC time is always greater than or equal to the wall time. You can find more detail in the HLC paper.

In terms of transactions, the gateway node picks a timestamp for the transaction using HLC time. Whenever a transaction's timestamp is mentioned, it's an HLC value. This timestamp is used to both track versions of values (through multi-version concurrency control), as well as provide our transactional isolation guarantees.

When nodes send requests to other nodes, they include the timestamp generated by their local HLCs (which includes both physical and logical components). When nodes receive requests, they inform their local HLC of the timestamp supplied with the event by the sender. This is useful in guaranteeing that all data read/written on a node is at a timestamp less than the next HLC time.

This then lets the node primarily responsible for the range (i.e., the leaseholder) serve reads for data it stores by ensuring the transaction reading the data is at an HLC time greater than the MVCC value it's reading (i.e., the read always happens "after" the write).

Max clock offset enforcement

CockroachDB requires moderate levels of clock synchronization to preserve data consistency. For this reason, when a node detects that its clock is out of sync with at least half of the other nodes in the cluster by 80% of the maximum offset allowed, it crashes immediately.

While serializable consistency is maintained regardless of clock skew, skew outside the configured clock offset bounds can result in violations of single-key linearizability between causally dependent transactions. It's therefore important to prevent clocks from drifting too far by running NTP or other clock synchronization software on each node.

For more detail about the risks that large clock offsets can cause, see What happens when node clocks are not properly synchronized?

Timestamp cache

As part of providing serializability, whenever an operation reads a value, we store the operation's timestamp in a timestamp cache, which shows the high-water mark for values being read.

The timestamp cache is a data structure used to store information about the reads performed by leaseholders. This is used to ensure that once some transaction t1 reads a row, another transaction t2 that comes along and tries to write to that row will be ordered after t1, thus ensuring a serial order of transactions, aka serializability.

Whenever a write occurs, its timestamp is checked against the timestamp cache. If the timestamp is earlier than the timestamp cache's latest value, CockroachDB will attempt to push the timestamp for its transaction forward to a later time. Pushing the timestamp might cause the transaction to restart during the commit time of the transaction (see read refreshing).

Closed timestamps

Each CockroachDB range tracks a property called its closed timestamp, which means that no new writes can ever be introduced at or below that timestamp. The closed timestamp is advanced continuously on the leaseholder, and lags the current time by some target interval. As the closed timestamp is advanced, notifications are sent to each follower. If a range receives a write at a timestamp less than or equal to its closed timestamp, the write is forced to change its timestamp, which might result in a transaction retry error (see read refreshing).

In other words, a closed timestamp is a promise by the range's leaseholder to its follower replicas that it will not accept writes below that timestamp. Generally speaking, the leaseholder continuously closes timestamps a few seconds in the past.

The closed timestamps subsystem works by propagating information from leaseholders to followers by piggybacking closed timestamps onto Raft commands such that the replication stream is synchronized with timestamp closing. This means that a follower replica can start serving reads with timestamps at or below the closed timestamp as soon as it has applied all of the Raft commands up to the position in the Raft log specified by the leaseholder.

Once the follower replica has applied the abovementioned Raft commands, it has all the data necessary to serve reads with timestamps less than or equal to the closed timestamp.

Note that closed timestamps are valid even if the leaseholder changes, since they are preserved across lease transfers. Once a lease transfer occurs, the new leaseholder will not break the closed timestamp promise made by the old leaseholder.

Closed timestamps provide the guarantees that are used to provide support for low-latency historical (stale) reads, also known as Follower Reads. Follower reads can be particularly useful in multi-region deployments.

The timestamp for any transaction, especially a long-running transaction, could be pushed. An example is when a transaction encounters a key written at a higher timestamp. When this kind of contention happens between transactions, the closed timestamp may provide some mitigation. Increasing the closed timestamp interval may reduce the likelihood that a long-running transaction's timestamp is pushed and must be retried. Thoroughly test any adjustment to the closed timestamp interval before deploying the change in production, because such an adjustment can have an impact on:

- Follower reads: Latency or throughput may be increased, because reads are served only by the leaseholder.

- Change data capture: Latency of changefeed messages may be increased.

- Statistics collection: Load placed on the leaseholder may increase during collection.

While increasing the closed timestamp may decrease retryable errors, it may also increase lock latencies. Consider an example where:

- The long-running transaction

txn 1holds write locks on keys at timet=1. - The long-running transaction

txn 2is waiting to read those same keys att=1.

The following scenarios may occur depending on whether or not the closed timestamp has been increased:

- When the timestamp for

txn 1is pushed forward by the closed timestamp, its writes are moved to timet=2, and it can try again to read the keys att=1before writing its changes att=2. The likelihood of retryable errors has increased. - If the closed timestamp interval is increased,

txn 2may need to wait fortxn 1to complete or to be pushed into the future beforetxn 2can proceed. The likelihood of lock contention has increased.

Before increasing the closed timestamp intervals, consider other solutions for minimizing transaction retries.

For more information about the implementation of closed timestamps and Follower Reads, see our blog post An Epic Read on Follower Reads.

client.Txn and TxnCoordSender

As we mentioned in the SQL layer's architectural overview, CockroachDB converts all SQL statements into key-value (KV) operations, which is how data is ultimately stored and accessed.

All of the KV operations generated from the SQL layer use client.Txn, which is the transactional interface for the CockroachDB KV layer––but, as we discussed above, all statements are treated as transactions, so all statements use this interface.

However, client.Txn is actually just a wrapper around TxnCoordSender, which plays a crucial role in our code base by:

- Dealing with transactions' state. After a transaction is started,

TxnCoordSenderstarts asynchronously sending heartbeat messages to that transaction's transaction record, which signals that it should be kept alive. If theTxnCoordSender's heartbeating stops, the transaction record is moved to theABORTEDstatus. - Tracking each written key or key range over the course of the transaction.

- Clearing the accumulated write intent for the transaction when it's committed or aborted. All of a transaction's operations go through the same

TxnCoordSenderto account for all of its write intents and to optimize the cleanup process.

After setting up this bookkeeping, the request is passed to the DistSender in the distribution layer.

Transaction records

To track the status of a transaction's execution, we write a value called a transaction record to our key-value store. All of a transaction's write intents point back to this record, which lets any transaction check the status of any write intents it encounters. This kind of canonical record is crucial for supporting concurrency in a distributed environment.

Transaction records are always written to the same range as the first key in the transaction, which is known by the TxnCoordSender. However, the transaction record itself isn't created until one of the following conditions occur:

- The write operation commits

- The

TxnCoordSenderheartbeats the transaction - An operation forces the transaction to abort

Given this mechanism, the transaction record uses the following states:

PENDING: Indicates that the write intent's transaction is still in progress.COMMITTED: Once a transaction has completed, this status indicates that write intents can be treated as committed values.STAGING: Used to enable the Parallel Commits feature. Depending on the state of the write intents referenced by this record, the transaction may or may not be in a committed state.ABORTED: Indicates that the transaction was aborted and its values should be discarded.- Record does not exist: If a transaction encounters a write intent whose transaction record doesn't exist, it uses the write intent's timestamp to determine how to proceed. If the write intent's timestamp is within the transaction liveness threshold, the write intent's transaction is treated as if it is

PENDING, otherwise it's treated as if the transaction isABORTED.

The transaction record for a committed transaction remains until all its write intents are converted to MVCC values.

Write intents

Values in CockroachDB are not written directly to the storage layer; instead values are written in a provisional state known as a "write intent." These are essentially MVCC records with an additional value added to them which identifies the transaction record to which the value belongs. They can be thought of as a combination of a replicated lock and a replicated provisional value.

Whenever an operation encounters a write intent (instead of an MVCC value), it looks up the status of the transaction record to understand how it should treat the write intent value. If the transaction record is missing, the operation checks the write intent's timestamp and evaluates whether or not it is considered expired.

CockroachDB manages concurrency control using a per-node, in-memory lock table. This table holds a collection of locks acquired by in-progress transactions, and incorporates information about write intents as they are discovered during evaluation. For more information, see the section below on Concurrency control.

Resolving write intents

Whenever an operation encounters a write intent for a key, it attempts to "resolve" it, the result of which depends on the write intent's transaction record:

COMMITTED: The operation reads the write intent and converts it to an MVCC value by removing the write intent's pointer to the transaction record.ABORTED: The write intent is ignored and deleted.PENDING: This signals there is a transaction conflict, which must be resolved.STAGING: This signals that the operation should check whether the staging transaction is still in progress by verifying that the transaction coordinator is still heartbeating the staging transaction’s record. If the coordinator is still heartbeating the record, the operation should wait. For more information, see Parallel Commits.- Record does not exist: If the write intent was created within the transaction liveness threshold, it's the same as

PENDING, otherwise it's treated asABORTED.

Concurrency control

The concurrency manager sequences incoming requests and provides isolation between the transactions that issued those requests that intend to perform conflicting operations. This activity is also known as concurrency control.

The concurrency manager combines the tasks of a latch manager and a lock table to accomplish this work:

- The latch manager sequences the incoming requests and provides isolation between those requests.

- The lock table provides both locking and sequencing of requests (in concert with the latch manager). It is a per-node, in-memory data structure that holds a collection of locks acquired by in-progress transactions. To ensure compatibility with the existing system of write intents (a.k.a. replicated, exclusive locks), it pulls in information about these external locks as necessary when they are discovered in the course of evaluating requests.

The concurrency manager enables support for pessimistic locking via SQL using the SELECT FOR UPDATE statement. This statement can be used to increase throughput and decrease tail latency for contended operations.

For more details about how the concurrency manager works with the latch manager and lock table, see the sections below:

Concurrency manager

The concurrency manager is a structure that sequences incoming requests and provides isolation between the transactions that issued those requests that intend to perform conflicting operations. During sequencing, conflicts are discovered and any found are resolved through a combination of passive queuing and active pushing. Once a request has been sequenced, it is free to evaluate without concerns of conflicting with other in-flight requests due to the isolation provided by the manager. This isolation is guaranteed for the lifetime of the request but terminates once the request completes.

Each request in a transaction should be isolated from other requests, both during the request's lifetime and after the request has completed (assuming it acquired locks), but within the surrounding transaction's lifetime.

The manager accommodates this by allowing transactional requests to acquire locks, which outlive the requests themselves. Locks extend the duration of the isolation provided over specific keys to the lifetime of the lock-holder transaction itself. They are (typically) only released when the transaction commits or aborts. Other requests that find these locks while being sequenced wait on them to be released in a queue before proceeding. Because locks are checked during sequencing, locks do not need to be checked again during evaluation.

However, not all locks are stored directly under the manager's control, so not all locks are discoverable during sequencing. Specifically, write intents (replicated, exclusive locks) are stored inline in the MVCC keyspace, so they are not detectable until request evaluation time. To accommodate this form of lock storage, the manager integrates information about external locks with the concurrency manager structure.

The concurrency manager operates on an unreplicated lock table structure. Unreplicated locks are held only on a single replica in a range, which is typically the leaseholder. They are very fast to acquire and release, but provide no guarantee of survivability across lease transfers or leaseholder crashes.

This lack of survivability for unreplicated locks affects SQL statements implemented using them, such as SELECT ... FOR UPDATE.

In the future, we intend to pull all locks, including those associated with write intents, into the concurrency manager directly through a replicated lock table structure.

Fairness is ensured between requests. In general, if any two requests conflict then the request that arrived first will be sequenced first. As such, sequencing guarantees first-in, first-out (FIFO) semantics. The primary exception to this is that a request that is part of a transaction which has already acquired a lock does not need to wait on that lock during sequencing, and can therefore ignore any queue that has formed on the lock. For other exceptions to this sequencing guarantee, see the lock table section below.

Lock table

The lock table is a per-node, in-memory data structure that holds a collection of locks acquired by in-progress transactions. Each lock in the table has a possibly-empty lock wait-queue associated with it, where conflicting transactions can queue while waiting for the lock to be released. Items in the locally stored lock wait-queue are propagated as necessary (via RPC) to the existing TxnWaitQueue, which is stored on the leader of the range's Raft group that contains the transaction record.

The database is read and written using "requests". Transactions are composed of one or more requests. Isolation is needed across requests. Additionally, since transactions represent a group of requests, isolation is needed across such groups. Part of this isolation is accomplished by maintaining multiple versions and part by allowing requests to acquire locks. Even the isolation based on multiple versions requires some form of mutual exclusion to ensure that a read and a conflicting lock acquisition do not happen concurrently. The lock table provides both locking and sequencing of requests (in concert with the use of latches).

Locks outlive the requests themselves and thereby extend the duration of the isolation provided over specific keys to the lifetime of the lock-holder transaction itself. They are (typically) only released when the transaction commits or aborts. Other requests that find these locks while being sequenced wait on them to be released in a queue before proceeding. Because locks are checked during sequencing, requests are guaranteed access to all declared keys after they have been sequenced. In other words, locks do not need to be checked again during evaluation.

Currently, not all locks are stored directly under lock table control. Some locks are stored as write intents in the MVCC layer, and are thus not discoverable during sequencing. Specifically, write intents (replicated, exclusive locks) are stored inline in the MVCC keyspace, so they are often not detectable until request evaluation time. To accommodate this form of lock storage, the lock table adds information about these locks as they are encountered during evaluation. In the future, we intend to pull all locks, including those associated with write intents, into the lock table directly.

The lock table also provides fairness between requests. If two requests conflict then the request that arrived first will typically be sequenced first. There are some exceptions:

A request that is part of a transaction which has already acquired a lock does not need to wait on that lock during sequencing, and can therefore ignore any queue that has formed on the lock.

Contending requests that encounter different levels of contention may be sequenced in non-FIFO order. This is to allow for greater concurrency. For example, if requests R1 and R2 contend on key K2, but R1 is also waiting at key K1, R2 may slip past R1 and evaluate.

Latch manager

The latch manager sequences incoming requests and provides isolation between those requests under the supervision of the concurrency manager.

The way the latch manager works is as follows:

As write requests occur for a range, the range's leaseholder serializes them; that is, they are placed into some consistent order.

To enforce this serialization, the leaseholder creates a "latch" for the keys in the write value, providing uncontested access to the keys. If other requests come into the leaseholder for the same set of keys, they must wait for the latch to be released before they can proceed.

Read requests also generate latches. Multiple read latches over the same keys can be held concurrently, but a read latch and a write latch over the same keys cannot.

Another way to think of a latch is like a mutex which is only needed for the duration of a single, low-level request. To coordinate longer-running, higher-level requests (i.e., client transactions), we use a durable system of write intents.

Isolation levels

Isolation is an element of ACID transactions, which determines how concurrency is controlled, and ultimately guarantees consistency.

CockroachDB executes all transactions at the strongest ANSI transaction isolation level: SERIALIZABLE. All other ANSI transaction isolation levels (e.g., SNAPSHOT, READ UNCOMMITTED, READ COMMITTED, and REPEATABLE READ) are automatically upgraded to SERIALIZABLE. Weaker isolation levels have historically been used to maximize transaction throughput. However, recent research has demonstrated that the use of weak isolation levels results in substantial vulnerability to concurrency-based attacks.

CockroachDB now only supports SERIALIZABLE isolation. In previous versions of CockroachDB, you could set transactions to SNAPSHOT isolation, but that feature has been removed.

SERIALIZABLE isolation does not allow any anomalies in your data, and is enforced by requiring the client to retry transactions if serializability violations are possible.

Transaction conflicts

CockroachDB's transactions allow the following types of conflicts that involve running into an intent:

- Write/write, where two

PENDINGtransactions create write intents for the same key. - Write/read, when a read encounters an existing write intent with a timestamp less than its own.

To make this simpler to understand, we'll call the first transaction TxnA and the transaction that encounters its write intents TxnB.

CockroachDB proceeds through the following steps:

If the transaction has an explicit priority set (i.e.,

HIGHorLOW), the transaction with the lower priority is aborted (in the write/write case) or has its timestamp pushed (in the write/read case).If the encountered transaction is expired, it's

ABORTEDand conflict resolution succeeds. We consider a write intent expired if:- It doesn't have a transaction record and its timestamp is outside of the transaction liveness threshold.

- Its transaction record hasn't been heartbeated within the transaction liveness threshold.

TxnBenters theTxnWaitQueueto wait forTxnAto complete.

Additionally, the following types of conflicts that do not involve running into intents can arise:

- Write after read, when a write with a lower timestamp encounters a later read. This is handled through the timestamp cache.

- Read within uncertainty window, when a read encounters a value with a higher timestamp but it's ambiguous whether the value should be considered to be in the future or in the past of the transaction because of possible clock skew. This is handled by attempting to push the transaction's timestamp beyond the uncertain value (see read refreshing). Note that, if the transaction has to be retried, reads will never encounter uncertainty issues on any node which was previously visited, and that there's never any uncertainty on values read from the transaction's gateway node.

TxnWaitQueue

The TxnWaitQueue tracks all transactions that could not push a transaction whose writes they encountered, and must wait for the blocking transaction to complete before they can proceed.

The TxnWaitQueue's structure is a map of blocking transaction IDs to those they're blocking. For example:

txnA -> txn1, txn2

txnB -> txn3, txn4, txn5

Importantly, all of this activity happens on a single node, which is the leader of the range's Raft group that contains the transaction record.

Once the transaction does resolve––by committing or aborting––a signal is sent to the TxnWaitQueue, which lets all transactions that were blocked by the resolved transaction begin executing.

Blocked transactions also check the status of their own transaction to ensure they're still active. If the blocked transaction was aborted, it's simply removed.

If there is a deadlock between transactions (i.e., they're each blocked by each other's Write Intents), one of the transactions is randomly aborted. In the above example, this would happen if TxnA blocked TxnB on key1 and TxnB blocked TxnA on key2.

Read refreshing

Whenever a transaction's timestamp has been pushed, additional checks are required before allowing it to commit at the pushed timestamp: any values which the transaction previously read must be checked to verify that no writes have subsequently occurred between the original transaction timestamp and the pushed transaction timestamp. This check prevents serializability violation.

The check is done by keeping track of all the reads using a dedicated RefreshRequest. If this succeeds, the transaction is allowed to commit (transactions perform this check at commit time if they've been pushed by a different transaction or by the timestamp cache, or they perform the check whenever they encounter a ReadWithinUncertaintyIntervalError immediately, before continuing). If the refreshing is unsuccessful (also known as read invalidation), then the transaction must be retried at the pushed timestamp.

Transaction pipelining

Transactional writes are pipelined when being replicated and when being written to disk, dramatically reducing the latency of transactions that perform multiple writes. For example, consider the following transaction:

-- CREATE TABLE kv (id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(), key VARCHAR, value VARCHAR);

> BEGIN;

INSERT into kv (key, value) VALUES ('apple', 'red');

INSERT into kv (key, value) VALUES ('banana', 'yellow');

INSERT into kv (key, value) VALUES ('orange', 'orange');

COMMIT;

With transaction pipelining, write intents are replicated from leaseholders in parallel, so the waiting all happens at the end, at transaction commit time.

At a high level, transaction pipelining works as follows:

For each statement, the transaction gateway node communicates with the leaseholders (L1, L2, L3, ..., Li) for the ranges it wants to write to. Since the primary keys in the table above are UUIDs, the ranges are probably split across multiple leaseholders (this is a good thing, as it decreases transaction conflicts).

Each leaseholder Li receives the communication from the transaction gateway node and does the following in parallel:

- Creates write intents and sends them to its follower nodes.

- Responds to the transaction gateway node that the write intents have been sent. Note that replication of the intents is still in-flight at this stage.

When attempting to commit, the transaction gateway node then waits for the write intents to be replicated in parallel to all of the leaseholders' followers. When it receives responses from the leaseholders that the write intents have propagated, it commits the transaction.

In terms of the SQL snippet shown above, all of the waiting for write intents to propagate and be committed happens once, at the very end of the transaction, rather than for each individual write. This means that the cost of multiple writes is not O(n) in the number of SQL DML statements; instead, it's O(1).

Parallel Commits

Parallel Commits is an optimized atomic commit protocol that cuts the commit latency of a transaction in half, from two rounds of consensus down to one. Combined with transaction pipelining, this brings the latency incurred by common OLTP transactions to near the theoretical minimum: the sum of all read latencies plus one round of consensus latency.

Under this atomic commit protocol, the transaction coordinator can return to the client eagerly when it knows that the writes in the transaction have succeeded. Once this occurs, the transaction coordinator can set the transaction record's state to COMMITTED and resolve the transaction's write intents asynchronously.

The transaction coordinator is able to do this while maintaining correctness guarantees because it populates the transaction record with enough information (via a new STAGING state, and an array of in-flight writes) for other transactions to determine whether all writes in the transaction are present, and thus prove whether or not the transaction is committed.

For an example showing how Parallel Commits works in more detail, see Parallel Commits - step by step.

The latency until intents are resolved is unchanged by the introduction of Parallel Commits: two rounds of consensus are still required to resolve intents. This means that contended workloads are expected to profit less from this feature.

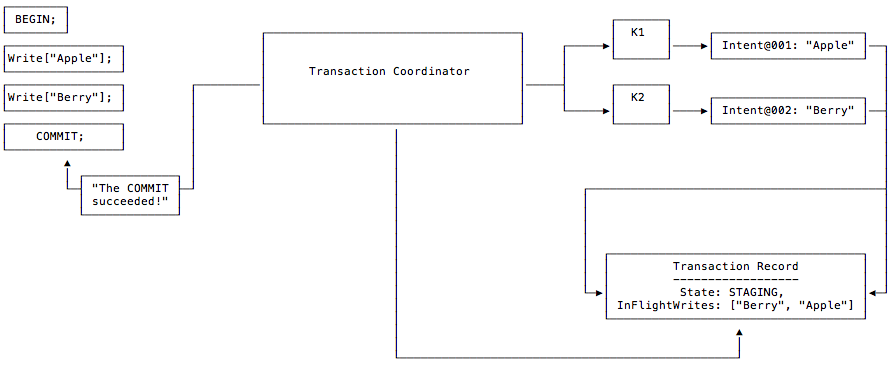

Parallel Commits - step by step

This section contains a step-by-step example of a transaction that writes its data using the Parallel Commits atomic commit protocol and does not encounter any errors or conflicts.

Step 1

The client starts the transaction. A transaction coordinator is created to manage the state of that transaction.

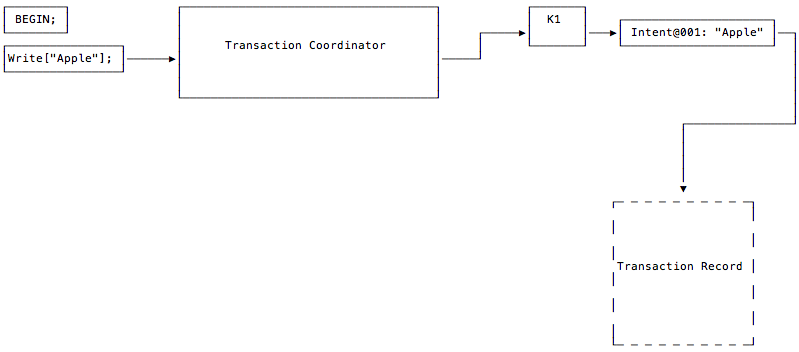

Step 2

The client issues a write to the "Apple" key. The transaction coordinator begins the process of laying down a write intent on the key where the data will be written. The write intent has a timestamp and a pointer to an as-yet nonexistent transaction record. Additionally, each write intent in the transaction is assigned a unique sequence number which is used to uniquely identify it.

The coordinator avoids creating the record for as long as possible in the transaction's lifecycle as an optimization. The fact that the transaction record does not yet exist is denoted in the diagram by its dotted lines.

The coordinator does not need to wait for write intents to replicate from leaseholders before moving on to the next statement from the client, since that is handled in parallel by Transaction Pipelining.

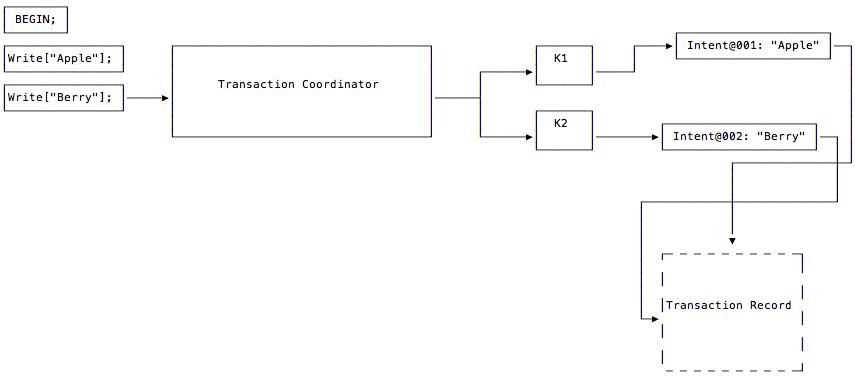

Step 3

The client issues a write to the "Berry" key. The transaction coordinator lays down a write intent on the key where the data will be written. This write intent has a pointer to the same transaction record as the intent created in Step 2, since these write intents are part of the same transaction.

As before, the coordinator does not need to wait for write intents to replicate from leaseholders before moving on to the next statement from the client.

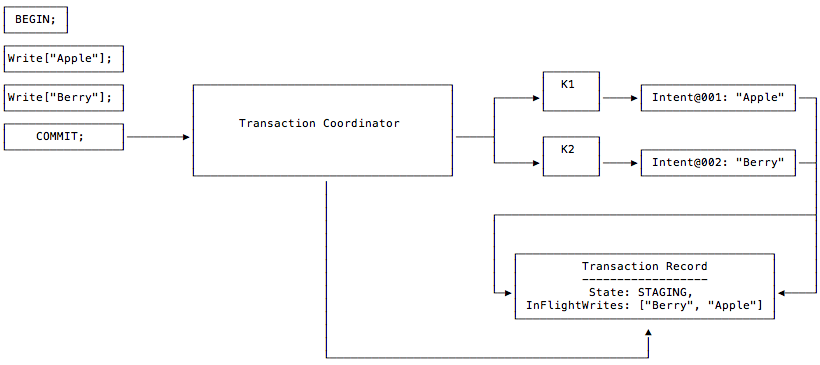

Step 4

The client issues a request to commit the transaction's writes. The transaction coordinator creates the transaction record and immediately sets the record's state to STAGING, and records the keys of each write that the transaction has in flight.

It does this without waiting to see whether the writes from Steps 2 and 3 have succeeded.

Step 5

The transaction coordinator, having received the client's COMMIT request, waits for the pending writes to succeed (i.e., be replicated across the cluster). Once all of the pending writes have succeeded, the coordinator returns a message to the client, letting it know that its transaction has committed successfully.

The transaction is now considered atomically committed, even though the state of its transaction record is still STAGING. The reason this is still considered an atomic commit condition is that a transaction is considered committed if it is one of the following logically equivalent states:

The transaction record's state is

STAGING, and its list of pending writes have all succeeded (i.e., theInFlightWriteshave achieved consensus across the cluster). Any observer of this transaction can verify that its writes have replicated. Transactions in this state are implicitly committed.The transaction record's state is

COMMITTED. Transactions in this state are explicitly committed.

Despite their logical equivalence, the transaction coordinator now works as quickly as possible to move the transaction record from the STAGING to the COMMITTED state so that other transactions do not encounter a possibly conflicting transaction in the STAGING state and then have to do the work of verifying that the staging transaction's list of pending writes has succeeded. Doing that verification (also known as the "transaction status recovery process") would be slow.

Additionally, when other transactions encounter a transaction in STAGING state, they check whether the staging transaction is still in progress by verifying that the transaction coordinator is still heartbeating that staging transaction’s record. If the coordinator is still heartbeating the record, the other transactions will wait, on the theory that letting the coordinator update the transaction record with the result of the attempt to commit will be faster than going through the transaction status recovery process. This means that in practice, the transaction status recovery process is only used if the transaction coordinator dies due to an untimely crash.

Non-blocking transactions

CockroachDB supports low-latency, global reads of read-mostly data in multi-region clusters using non-blocking transactions: an extension of the standard read-write transaction protocol that allows a writing transaction to perform locking in a manner such that contending reads by other transactions can avoid waiting on its locks.

The non-blocking transaction protocol and replication scheme differ from standard read-write transactions as follows:

- Non-blocking transactions use a replication scheme over the ranges they operate on that allows all followers in these ranges to serve consistent (non-stale) reads.

- Non-blocking transactions are minimally disruptive to reads over the data they modify, even in the presence of read/write contention.

These properties of non-blocking transactions combine to provide predictable read latency for a configurable subset of data in global deployments. This is useful since there exists a sizable class of data which is heavily skewed towards read traffic.

Most users will not interact with the non-blocking transaction mechanism directly. Instead, they will set a GLOBAL table locality using the SQL API.

How non-blocking transactions work

The consistency guarantees offered by non-blocking transactions are enforced through semi-synchronized clocks with bounded uncertainty, not inter-node communication, since the latter would struggle to provide the same guarantees without incurring excessive latency costs in global deployments.

Non-blocking transactions are implemented via non-blocking ranges. Every non-blocking range has the following properties:

- Any transaction that writes to this range has its write timestamp pushed into the future.

- The range is able to propagate a closed timestamp in the future of present time.

- A transaction that writes to this range and commits with a future time commit timestamp needs to wait until the HLC advances past its commit timestamp. This process is known as "commit-wait". Essentially, the HLC waits until it advances past the future timestamp on its own, or it advances due to updates from other timestamps.

- A transaction that reads a future-time write to this range can have its commit timestamp bumped into the future as well, if the write falls in the read's uncertainty window (this is dictated by the maximum clock offset configured for the cluster). Such transactions (a.k.a. "conflicting readers") may also need to commit-wait.

As a result of the above properties, all replicas in a non-blocking range are expected to be able to serve transactionally-consistent reads at the present. This means that all follower replicas in a non-blocking range (which includes all non-voting replicas) implicitly behave as "consistent read replicas", which are exactly what they sound like: read-only replicas that always have a consistent view of the range's current state.

Technical interactions with other layers

Transaction and SQL layer

The transaction layer receives KV operations from planNodes executed in the SQL layer.

Transaction and distribution layer

The TxnCoordSender sends its KV requests to DistSender in the distribution layer.

What's next?

Learn how CockroachDB presents a unified view of your cluster's data in the distribution layer.